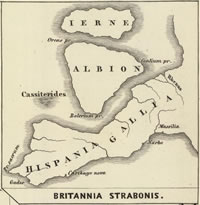

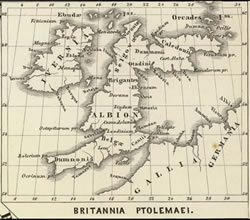

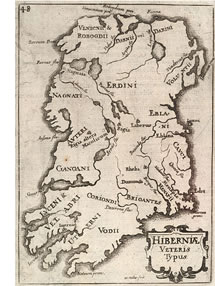

Wexford Harbour was well known as a trading base and a monastic settlement long before the Norse arrived. It is not apparent on the earliest available map showing Ireland (Ierne) which was published by the Greek historian, geographer and philosopher Strabo in the 1st century AD. The geography of these islands appears to have been poorly known at the time. However, only a century later, Ptolemy published a vastly superior map of Britannia showing Ireland (Ivernia), England (Albion), Scotland (Caledonii), France (Gallia) and Germany (Germania). These countries are all recognisable and similar in shape and relative position to their modern counterparts.

Ptolemy was an astronomer, mathematician and geographer, and brought all of his skills to mapping of the known world. He clearly had access to a wealth of information about Ireland as he was able to reference and locate 15 rivers, six promontories and ten cities deriving their latitude and longitude into the bargain. It is now known that Dabrona equates to the River Lee, Bargus to the River Barrow, Manapia to Wexford and Eblana to Dublin. Although Ptolemy shows Manapia somewhat north of its correct position, his map shows a large haven or harbour close to the town which must be Wexford Harbour.

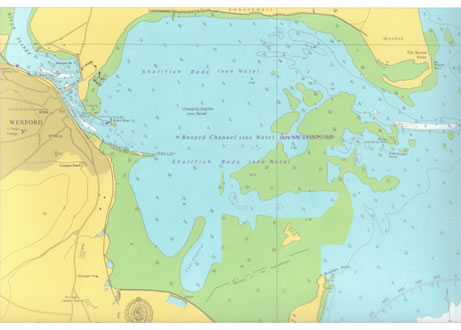

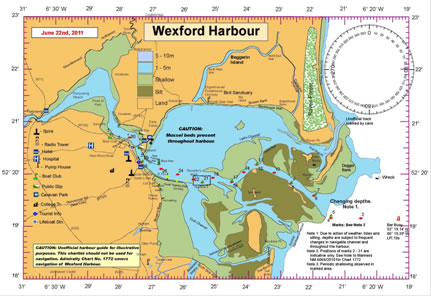

In earlier times, the area occupied by the harbour was considerably larger than it is today. The large island of Beggerin was known to be a safe refuge for early Christian settlements. The name Wexford is derived from "Waesfiord" given by the Norse raiders who arrived in 819. The meaning of this early name is disputed; it may have meant 'broad shallow bay' or it may have been a corruption of another Norse term meaning 'fiord of the waterlogged land' or 'fiord of the mud flats'. The Norse longboats were shallow draft vessels; this allowed them to safely negotiate this harbour of islands, shallow narrow channels and mudflats that described then and still describes Wexford Harbour.

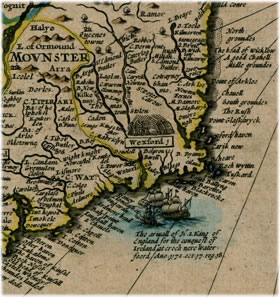

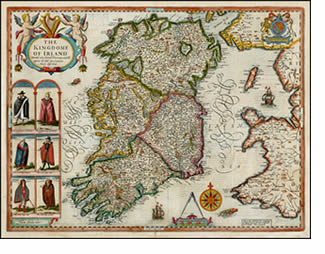

Over the course of about 300 years, the Norse settled in Wexford, intermarried with the local population and gradually converted to Christianity. They forged temporary alliances with Irish kings, sometimes fighting with other Norse towns; at other times, such as in 933 and 1161 they were attacked by the Irish. The Norse remained in control until 1169 AD when Wexford was attacked by a superior force of Norman and Irish soldiers. There was a short battle after which the Hiberno-Norse withdrew within the walls leaving their ships unprotected. These were set on fire by the attackers - this may have been the origin of the Wexford Town crest, the three burning ships. Next day the Norsemen conceded defeat and accepted peace terms. Much of their lands and property was confiscated; a small number of Norse - perhaps 30 or 40 - settled in Rosslare peninsula but these gradually died out. From then on, apart from a few brief respites, Wexford and its harbour largely remained under Norman, Anglo-Norman or British influence until Irish independence. The battle is depicted in the clip from Speed's 1601 map of "Invasions of England and Ireland with al their Civil Wars Since the Conquest". (sic)

The Wexford inhabitants, whether of Norse or Irish ancestry were not very enthusiastic about their Anglo-Norman overlords and engaged in periodic bouts of resistance.

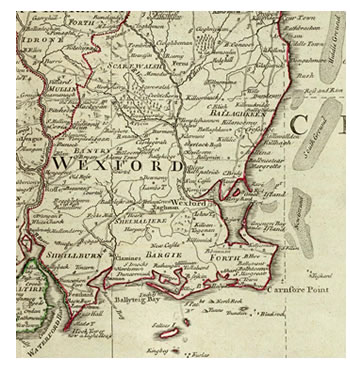

In the fifteenth century, settlers of English extraction were largely confined to the southern baronies of Forth, Bargy and Shelburne, insulated as they were by natural defences such as Forth Mountain and the Corock and Owenduff rivers. The English had been routed from North Wexford, indeed the English in Dublin now largely resided within the protective earthworks known as the Pale. Wexford became a major maritime port exporting fish, cloth, wool and hides. It was Ireland's leading fishing port in the fifteenth and sixteenth century exporting mainly to ports along the west coast of England and Wales.

In 1642, the Dublin government in a dispatch from London described Wexford as "a place plentiful in ships and seamen, and where the rebels have set up Spanish colours on their walls in defiance of the kings and kingdom of England, and have gotten in from foreign parts great stores of arms and ammunition".

It is no coincidence that this was one year after the Irish Rebellion of 1641 when Flemish mariners were encouraged to use Wexford Harbour to attack British ships passing along the Irish Sea from ports Whitehaven to Bristol and even in the English Channel. Wexford Harbour was a marvellous base for operations; it was strategically located at the junction of the Irish Sea, the Western Approaches of the English Channel and the Atlantic Ocean. The difficult navigation of the harbour gave security to the locals, as larger attacking ships could not enter. The sandbanks and narrow channels did not present much difficulty to the Dunkirk frigates or the local shallow draft cargo ships. The opening up of the New World meant that Ireland was centre-stage in the North Atlantic. The Irish had not embraced the reformation and had more in common with the Catholic French and Spanish than they did with the English to the east.

In 1649, a parliamentary army under Oliver Cromwell landed in Dublin and after some months set out to conquer Wexford. An army of 7000 foot soldiers and 2000 cavalry camped north of the town and sent a detachment to capture Rosslare fort at the mouth of the harbour. This enabled Cromwell's fleet to enter the harbour unopposed. The army moved to south of the town and bombarded Wexford Castle. Initially, Cromwell issued a summons to surrender on 3 October 1649, offering lenient terms in the hope that he could secure Wexford intact and use it as winter quarters for his troops. The mayor, aldermen and many citizens of Wexford were prepared to surrender but the military commander played for time. When both sides met to agree terms, the Irish side attempted to add a further set of proposals including the safe exit of the privateers with their goods and ships intact. Cromwell lost patience and talks broke down.

Ormond's troops made a stand in the market square, but they were quickly overwhelmed. Cromwell and his officers made no attempt to restrain their soldiers, who slaughtered the Wexford defenders and plundered the town. Hundreds of civilians were shot or drowned as they tried to escape the carnage by fleeing across the River Slaney. Wexford harbour provided the Parliamentarians with a naval base in southern Ireland where further supplies from southern England could be received. The Irish privateering fleet was finally broken up. Afterwards, Cromwell expressed no remorse for the massacre of civilians at Wexford in his report to Parliament. He regarded it as a further judgment upon the perpetrators of the Catholic uprising of 1641 and also upon the pirates who had operated out of Wexford harbour. His principal regret was that the town was so badly damaged during the sack that it was no longer suitable as winter quarters.

The sacking of Wexford was but a part of the re-conquest of the Irish Confederates by the English Parliamentarians.

The sacking of Wexford was but a part of the re-conquest of the Irish Confederates by the English Parliamentarians.

It resulted in massive dispossession of land from Irish ownership to English planters.

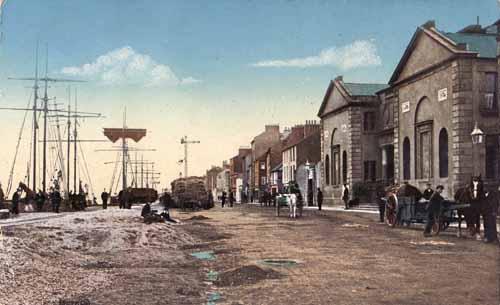

However the town itself remained relatively prosperous and continued its tradition as a major trading post and exporter of fish and agricultural products to the rest of the world.

In 1764 the historian Amyas Griffith wrote that Wexford's chief export was corn (2 Million barrels per year), herrings, beer, beef, hides, tallow, butter etc. and they trade to all parts of the globe but in particular to Liverpool, Barbados, Dublin, Norway and Bordeaux.

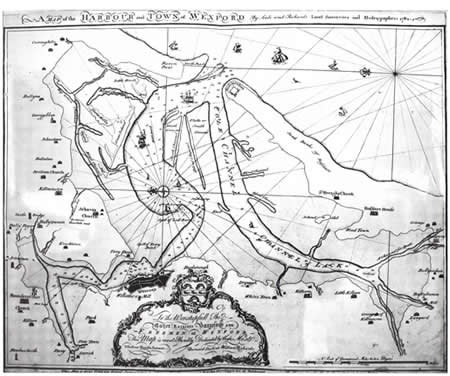

The town continued to experience expansion and economic growth and in 1772 two important bodies were set up - the Quay Corporation with full responsibility for shipping, quays and harbour and the Bridge Corporation to build two bridges across the Slaney at Wexford and Ferrycarrig. By 1788, Wexford, with 44 cargo ships and 200 herring boats was the sixth busiest port in Ireland. However the dangerous state of the harbour was a major impediment to trade. A new body - The Corporation for the Improvement of the Bar, Town & Harbour of Wexford was set up to improve and enhance the channel and to build quays, wharves and docks. This later became the Ballast Office of the Port of Wexford. Wexford Bridge was completed in 1795; Ferrycarrig Bridge shortly afterwards.

Although many parts of Ireland were affected by the 1798 Rebellion, the fighting in Wexford was by far the most widespread and brutal. Wexford was very closely linked to Dublin through trade and by the end of the eighteenth century it was mostly English speaking. The United Irishmen were very active in Dublin and in Belfast. However, they also had a strong network in Wexford. In fact, the rebels in Wexford were probably the most organised and successful in the country during the uprising.

The original plan of the United Irishmen had been to take Dublin on 23 May 1798 and then signal for the surrounding counties to rise up. However, the British Government was informed of this plan by spies and filled the main points of the city with troops. Therefore, the Dublin rising never got off the ground. Despite this, the signal was still given for the surrounding counties to go ahead. Three days later news of more government brutality against suspected rebels reached into Wexford.

Although many parts of Ireland were affected by the 1798 Rebellion, the fighting in Wexford was by far the most widespread and brutal. Wexford was very closely linked to Dublin through trade and by the end of the eighteenth century it was mostly English speaking. The United Irishmen were very active in Dublin and in Belfast. However, they also had a strong network in Wexford. In fact, the rebels in Wexford were probably the most organised and successful in the country during the uprising.

The original plan of the United Irishmen had been to take Dublin on 23 May 1798 and then signal for the surrounding counties to rise up. However, the British Government was informed of this plan by spies and filled the main points of the city with troops. Therefore, the Dublin rising never got off the ground. Despite this, the signal was still given for the surrounding counties to go ahead. Three days later news of more government brutality against suspected rebels reached into Wexford.

Fighting began in earnest in Wexford. Both sides suffered casualties of about 100 each in two separate battles on 27 May. The rebel forces were led by prominent Wexford United Irishmen. Father John Murphy, a Catholic priest, is regarded by some as one of the most inspirational of the rebel leaders of 1798. His followers were made up of various farmers and townspeople. Most of these were totally untrained in combat. On 28 May, the rebel forces had grown to several thousand people. They started to make their way to Wexford town.

Fighting began in earnest in Wexford. Both sides suffered casualties of about 100 each in two separate battles on 27 May. The rebel forces were led by prominent Wexford United Irishmen. Father John Murphy, a Catholic priest, is regarded by some as one of the most inspirational of the rebel leaders of 1798. His followers were made up of various farmers and townspeople. Most of these were totally untrained in combat. On 28 May, the rebel forces had grown to several thousand people. They started to make their way to Wexford town.

Having easily beaten the government garrison at Enniscorthy and destroyed the town, the rebel troop arrived at Wexford town on 30 May. By this stage, the 1,200 government troops had retreated from the town with their weapons, so they entered unopposed. The heart of the county was now in rebel control. The military leaders appointed a Grand National Committee and a Council of Elders to lead the rebels. These bodies included Catholic and Anglican merchants and landlords. They also formed the Wexford Army and the Wexford Navy. The navy consisted of four oyster boats each with a twenty five man crew. John Howlin, former privateer in the American War of Independence, was appointed Admiral. The next day, a ship carrying a colonel of the North Cork Militia was captured by the navy at the harbour's mouth. This was to play an important part in the Republic's capitulation three weeks later. The navy captured food and even gunpowder to aid in military operations. The so called Senate remained in control of Wexford town for three weeks in early summer 1798, a period that is sometimes referred to as that of the 'Wexford Republic'.

Having easily beaten the government garrison at Enniscorthy and destroyed the town, the rebel troop arrived at Wexford town on 30 May. By this stage, the 1,200 government troops had retreated from the town with their weapons, so they entered unopposed. The heart of the county was now in rebel control. The military leaders appointed a Grand National Committee and a Council of Elders to lead the rebels. These bodies included Catholic and Anglican merchants and landlords. They also formed the Wexford Army and the Wexford Navy. The navy consisted of four oyster boats each with a twenty five man crew. John Howlin, former privateer in the American War of Independence, was appointed Admiral. The next day, a ship carrying a colonel of the North Cork Militia was captured by the navy at the harbour's mouth. This was to play an important part in the Republic's capitulation three weeks later. The navy captured food and even gunpowder to aid in military operations. The so called Senate remained in control of Wexford town for three weeks in early summer 1798, a period that is sometimes referred to as that of the 'Wexford Republic'. By 19 June, the rebellion had petered out in most of the rest of the country. Wexford was one of the last remaining rebel strongholds. Thousands of reinforcements had arrived from Britain to boost the government army. The Battle of Vinegar Hill changed the course of the Wexford rebellion. The government army of 10,000 formed a ring around the hill. It bombarded the rebel headquarters with artillery. The bombardment soon became too much for the rebels, who managed to escape through a gap in the ring of attack chased by the government forces. Although most of the rebels got away, many were brutally murdered in the chase, even women and children. The surviving rebels were now scattered. After putting up a good fight, these Wexford rebels were finally defeated.

By 19 June, the rebellion had petered out in most of the rest of the country. Wexford was one of the last remaining rebel strongholds. Thousands of reinforcements had arrived from Britain to boost the government army. The Battle of Vinegar Hill changed the course of the Wexford rebellion. The government army of 10,000 formed a ring around the hill. It bombarded the rebel headquarters with artillery. The bombardment soon became too much for the rebels, who managed to escape through a gap in the ring of attack chased by the government forces. Although most of the rebels got away, many were brutally murdered in the chase, even women and children. The surviving rebels were now scattered. After putting up a good fight, these Wexford rebels were finally defeated.

Local decisions were implemented by the previously mentioned "Corporation for the Improvement of the Bar, Town & Harbour of Wexford". Clearly this body, which was set up in 1776 to improve and enhance the channel and to build quays, wharves and docks, concentrated its efforts on the quays and docks rather than navigation of the harbour. In the mediæval town of Wexford, the shore line was close to the present Main Street with houses backing onto the harbour and wharves extending out into the river. During the 18th century all of these wharves were buried under rock and new granite quay walls were constructed close to the present railway line. Indeed, the Crescent Quay was built on the site of the deep pool which had up to then been the favourite berthage of larger ships.

Local decisions were implemented by the previously mentioned "Corporation for the Improvement of the Bar, Town & Harbour of Wexford". Clearly this body, which was set up in 1776 to improve and enhance the channel and to build quays, wharves and docks, concentrated its efforts on the quays and docks rather than navigation of the harbour. In the mediæval town of Wexford, the shore line was close to the present Main Street with houses backing onto the harbour and wharves extending out into the river. During the 18th century all of these wharves were buried under rock and new granite quay walls were constructed close to the present railway line. Indeed, the Crescent Quay was built on the site of the deep pool which had up to then been the favourite berthage of larger ships.

However in an 1855 report to the House of Commons, it was regretted by Capt. James Vetch and Sir Francis Beaufort that the Commissioners had expended the shipping and harbour dues chiefly on building the quays of the town, erecting perches, and placing a few buoys, but little had been done to improve the channels. They also observed that the number of Commissioners to be appointed by statute was supposed to be 51 but the actual number was 104 and with such a numerous body of Commissioners and so constituted, no great good could be expected to arise. They recommended that in order to be able to make decisions and carry them out, the Corporation should be replaced by a commission of 12 persons who knew what they were about.

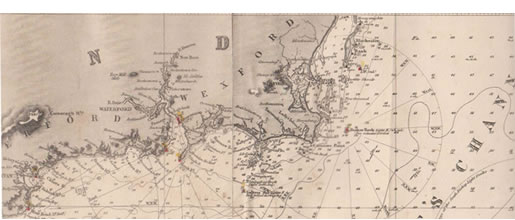

The Cubitt Report was just one of perhaps a dozen engineering reports on the improvement of Wexford Harbour presented to or sponsored by Westminster in the 18th and 19th centuries. He proposed to dig a channel through the Burrow at Rosslare joining the Coal Channel into the South Bay. He also made the comment that many of the merchants and shipowners in the port did not want to see improvements made. They had invested in shallow draught boats and improvements that allowed deep draught vessels into the harbour would damage their businesses. They were also concerned, he said, about the increased dues they would have to pay to meet the cost of improvements. Most were not implemented and those that were did little to improve navigation. The first attempt of land reclamation was made in 1814 by two Thomas brothers involving 800 acres of land on the SE side of the harbour. By 1816 the Thomas brothers had succeeded in building a bank that kept the sea out but a high tide caused the bank to crash, thus halting the reclamation works. In 1838, the engineer George Jack claimed that the earlier surveyors "...were ignorant of the true state of the coast and harbour of Wexford, and the causes of the formation of the bar; otherwise they could not have recommended plans for improvement which would have been totally ineffective".

The Cubitt Report was just one of perhaps a dozen engineering reports on the improvement of Wexford Harbour presented to or sponsored by Westminster in the 18th and 19th centuries. He proposed to dig a channel through the Burrow at Rosslare joining the Coal Channel into the South Bay. He also made the comment that many of the merchants and shipowners in the port did not want to see improvements made. They had invested in shallow draught boats and improvements that allowed deep draught vessels into the harbour would damage their businesses. They were also concerned, he said, about the increased dues they would have to pay to meet the cost of improvements. Most were not implemented and those that were did little to improve navigation. The first attempt of land reclamation was made in 1814 by two Thomas brothers involving 800 acres of land on the SE side of the harbour. By 1816 the Thomas brothers had succeeded in building a bank that kept the sea out but a high tide caused the bank to crash, thus halting the reclamation works. In 1838, the engineer George Jack claimed that the earlier surveyors "...were ignorant of the true state of the coast and harbour of Wexford, and the causes of the formation of the bar; otherwise they could not have recommended plans for improvement which would have been totally ineffective".

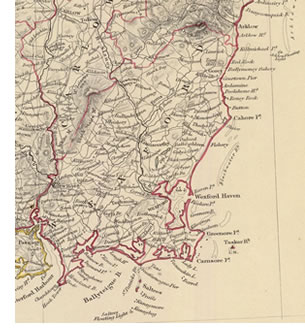

In 1846, John Edward Redmond and the other promoters got enabling legislation passed in the British parliament to reclaim the Slobs on behalf of the Wexford Harbour Improvement Company. While the ostensible reason for the reclamation was to improve the Harbour, it has also been described as a commercial land grab. All the engineering reports were ignored and the work proceeded despite significant opposition from the Wexford Harbour Commissioners. By 1849, 1,200 hectares of the North Slob had been embanked from Ardcavan to Raven Point. Work began on reclaiming the South Slob in 1854 and was completed some years later reducing the area of the harbour by a further 1,100 hectares.

Overall the area of the harbour was reduced by about 50% resulting in a tidal flow reduction of 570 million tons of water annually. Those who carried out the reclamation work either had no real understanding of the fundamental changes that would result from their work or perhaps they simply did not care. Whichever the reason, the results were not long in being felt. As early as 1857 the Harbour Commissioners were complaining about the increased silting. Further action was taken between 1882 and 1887 when two new breakwaters were constructed off the quays to train and concentrate the flow of the ebbing tide so that it would more effectively scour the shipping channel. These brought some improvement but they were not long enough to be fully effective.

Overall the area of the harbour was reduced by about 50% resulting in a tidal flow reduction of 570 million tons of water annually. Those who carried out the reclamation work either had no real understanding of the fundamental changes that would result from their work or perhaps they simply did not care. Whichever the reason, the results were not long in being felt. As early as 1857 the Harbour Commissioners were complaining about the increased silting. Further action was taken between 1882 and 1887 when two new breakwaters were constructed off the quays to train and concentrate the flow of the ebbing tide so that it would more effectively scour the shipping channel. These brought some improvement but they were not long enough to be fully effective. To make matters worse, in 1915, a severe south-easterly gale inundated Rosslare Spit necessitating construction of timber and stone groynes. These were only partly successful, and over the next 9 years gales continued to wreak havoc on the lifeboat station and the fort which were both located on Rosslare Spit. The RNLI made repeated requests for assistance from the railway company and from the Harbour Commissioners but no money was made available and RNLI were largely left to their own devices. Despite all of their efforts and a large expenditure of money, south-easterly gales in the winter of 1924 breached the spit in a number of places and Rosslare Fort was finally evacuated. During 1925 the breaches widened and eventually about 3.1 km of the Point was washed away

To make matters worse, in 1915, a severe south-easterly gale inundated Rosslare Spit necessitating construction of timber and stone groynes. These were only partly successful, and over the next 9 years gales continued to wreak havoc on the lifeboat station and the fort which were both located on Rosslare Spit. The RNLI made repeated requests for assistance from the railway company and from the Harbour Commissioners but no money was made available and RNLI were largely left to their own devices. Despite all of their efforts and a large expenditure of money, south-easterly gales in the winter of 1924 breached the spit in a number of places and Rosslare Fort was finally evacuated. During 1925 the breaches widened and eventually about 3.1 km of the Point was washed away

On the reclamation of the Slobs they went on: "the effect of these enclosures was to shut out so much of the tide as had formerly overflowed the area at high water springs. This great artificial reduction of the tidal reservoir capacity of the lagoon has undoubtedly had a most injurious effect upon the regime of the harbour and its sea approaches and was, in our decided opinion the primary cause of most of the troubles that followed." The report recommended the construction of new training walls all the way from the quays to Wexford Bar. The Irish government did not have the funds and this was shelved. Despite spasmodic dredging, the harbour continued to deteriorate.

In 1788, Wexford had 44 cargo ships and 200 herring boats and was the sixth busiest port in Ireland. Today there are no ships, no fishing boats; there are a dozen or so mussel dredgers and a scattering of half decker whelk boats. Unrestricted silting of the harbour has ensured that Wexford Port is now suitable only for shell fish harvesting and by leisure craft of fairly shallow draft.

It is difficult to predict what the future will hold for Wexford Harbour. In 2010, the Borough Council adopted as policy the refurbishment of the two breakwaters to their original height above high water springs. In the same year the responsibilities of Wexford Harbour Commissioners were transferred to Wexford County Council, a Harbour Master was appointed, a three year development budget was awarded. Improvements are already in place: channel navigation marks have been upgraded, other harbour works have commenced or are planned and it is proposed to attend to the training walls when funding is secured.

Research & Compilation:- B. Coulter

Corporation for the Improvement of the Bar, Town & Harbour of Wexford